|

The

Dangers of Moderate Drinking

By

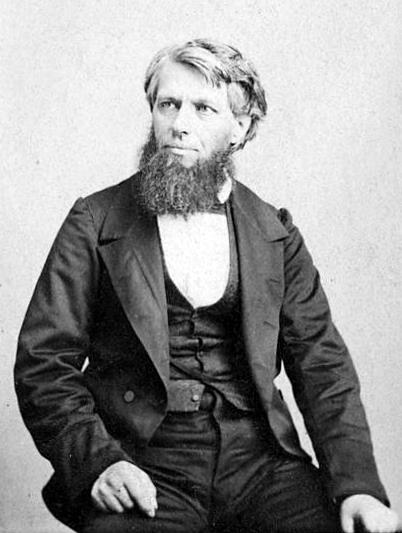

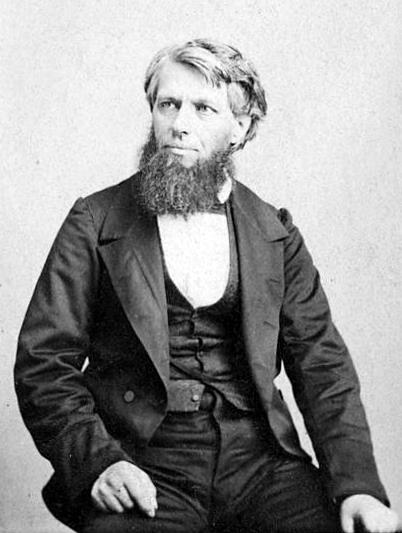

John B. Gough

John

B. Gough (1817-1886) Born in Sandgate, Kent, England in 1817,

Gough immigrated to the United States when he was only twelve years

old. His mother and sister also came to America. His mother died of

a stroke

and Gough, despondent, began to drink. He married in 1838. The couple

had a daughter but unfortunately, both mother and child died within

days of each other. By the age of 25, Gough was unemployed, homeless,

and

a confirmed drunkard. In 1842 he attended a temperance meeting in Worcester,

Massachusetts,

where he took a pledge to totally abstain from liquor. He began to

tell his story to eager audiences and soon embarked on a career of

lecturing

against the evils of drink. During his career, Gough delivered some

9,600 lectures to more than nine

million people in America, Canada, England, Scotland, and Ireland.

When

he died in 1886, the New York Times wrote that he "was probably

better known in this country and in Great Britain than any other

public speaker." Mr. Gough was one of this country’s most

influential social reformers who helped to solve one of America’s

most pressing problems. He was a witnessing Christian, a personal

friend of Charles Spurgeon, and shared the

pulpit in Boston (1877) during a "Temperance Day" meeting with D. L.

Moody.

For more info, see the Wikipedia entry for John B. Gough |

One favorite

argument of young men in reference to the use of intoxicating drink is, "When I

find out that it is doing me an injury, then I will give it up." That is

making an admission and coming to a conclusion.

One favorite

argument of young men in reference to the use of intoxicating drink is, "When I

find out that it is doing me an injury, then I will give it up." That is

making an admission and coming to a conclusion.

The admission is true; the conclusion

is false. You admit it may injure you, and when it has injured you, then

you will quit it. You won't use such an argument in reference to any other

matter. "I will put my hand into the den of a rattlesnake, and when I find

out that he has stuck his fangs into me I will draw it out and get it cured

as quickly as possible." There

is no common sense in that.

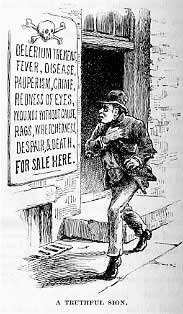

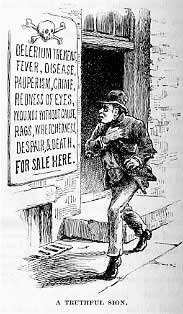

Young men, beware of this thing,

because it is a snare. It is fearfully deceptive. Every man who drinks intends

to be a moderate drinker. I have said this over and over again, because I

believe it to be important. Every man who becomes intemperate does so by a

course of

argument from

the beginning all the way down to ruin. Young men, you say, "When I find out that it is injuring

me, then I will give it up." Is that sensible?

I once heard of a pilot who said

he could pilot a vessel into Boston Harbor. "Now," said he to the

captain, "I'll stand 'midships, and you can take the helm. I know every rock in this channel -

every one of 'em - I know 'em all, and I'll give you warning." By and by the vessel struck upon a

rock, and the shock threw everybody down upon the deck. The poor pilot got up, rubbing

himself, and said, "Captain, there's one of 'em."

Now we say to young men, "There 's one of them. Hard up your helm before you strike!" That is

sensible. If you have struck, haul off and repair damages, and then strike again. Is that

sensible? In time the poor old battered hulk will not bear any more damages, and men will bury

you, a broken wreck. That is the end of it in many cases. "When I find out that it is injuring

me, then I will give it up." Gather all the drunkards of this country together, and ask them

every one, "Are you drinking enough to injure you?" A large proportion will

declare that they are not. Each one of them has become a drunkard in the

sight of God and man before he has

become one in his own estimation.

Intoxicating

drink is deceptive in its very nature. It reminds me of the fable of the serpent

in a circle of fire. A man was passing

by, and the snake said to him, "Help me out of my difficulty." "If I do,

you'll bite me." "Oh, no, I won't." "I'm afraid to trust you," "Help me out

of the fire, or it will consume me, and I promise on my word of honor I won't

bite

you." The man took the snake out of

the fire, and threw it on the ground. Instantly the serpent said, "Now I'll

bite you." "But didn't

you promise me you wouldn't?" "Yes, but don't you know it's my nature to

bite, and I cannot help it." So it is with the drink. It is its nature to

bite; it is its nature to deceive.

Intoxicating

drink is deceptive in its very nature. It reminds me of the fable of the serpent

in a circle of fire. A man was passing

by, and the snake said to him, "Help me out of my difficulty." "If I do,

you'll bite me." "Oh, no, I won't." "I'm afraid to trust you," "Help me out

of the fire, or it will consume me, and I promise on my word of honor I won't

bite

you." The man took the snake out of

the fire, and threw it on the ground. Instantly the serpent said, "Now I'll

bite you." "But didn't

you promise me you wouldn't?" "Yes, but don't you know it's my nature to

bite, and I cannot help it." So it is with the drink. It is its nature to

bite; it is its nature to deceive.

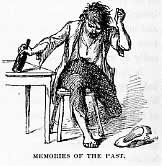

Young men say (and I have heard

them more than once) that they "must sow their wild oats."

Remember this, young gentlemen, "Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap." If you

sow corn, you reap corn. If you sow weeds, you reap weeds. If you sow to the flesh, you will of

the flesh reap corruption. But if you sow to the spirit, you will of the spirit reap life

everlasting. Ah, young men, look at that reaping, and then contemplate the awful reaping of men

to-day who are reaping as they have sown, in bitterness of spirit and anguish of soul. "When

I find out that it is injuring me, Then I will give it up."

Surely that is not common sense.

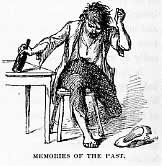

Such is the fascination thrown around a man by the power of this habit, that

it must have essentially injured him before he will acknowledge the hurt

and consent to give it up. Many a man has been struck down in his prosperity,

has

been sent to

prison for crime, before he acknowledged that his evil habit was injuring

him. I remember riding from Buffalo to Niagara Fails, and I said to a gentleman, "What

river is that, sir?"

"That," he said, "is Niagara River." "It is a beautiful stream," said I, "bright,

smooth, and glassy; how far off are the rapids?" " Only a few miles," was the

reply. "Is

it possible that only a few miles from us we shall find the water

in the turbulence which it must show when near the rapids?" "You will find

it so, sir."

And so I found it, and that first sight of Niagara Falls I shall never forget.

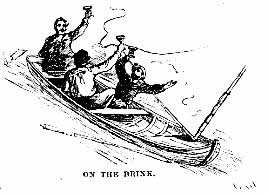

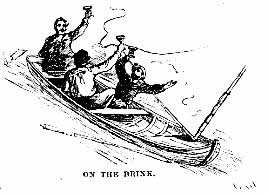

Now, launch your bark on that river; the water is smooth, beautiful, and glassy.

There is a ripple at the bow of

your boat, and the silvery wake it leaves behind adds to your enjoyment. You

set out on your pleasure excursion. Down the stream you glide; oars, sails,

and helm in proper trim. Suddenly

some one cries out from the bank, "Young men, ahoy!"

"What

is it?"

"What

is it?"

"The rapids are below you."

"Ha, ha! we have heard of the rapids, but we are not

such fools as to get into them. When we find we are going too fast, then we

shall up with the helm and steer to the shore; we will set the mast

in the socket, hoist the sail, and speed to land. Then on, boys, don't be alarmed,

there's no danger." "Young men, ahoy there! " "What is it?" "The rapids are

below you." "Ha, ha? we will

laugh and, quaff; all things delight us. What care we for the future? No man

ever saw it. Sufficient for the day is the evil thereof. We will enjoy life

while we may; we will catch

pleasure as it flies. This is enjoyment, time enough to steer out of danger

when we are sailing too swiftly with the current." "Young men, ahoy!" "What

is it?" "Beware, beware! the rapids

are below you." Now you feel them! See the water foaming all around! See

how fast you pass that point! Up with the helm!

Now turn! Pull hard; quick, quick! Pull for your lives! Pull till the blood

starts

from the nostrils and

the veins stand like whipcord upon the brow. Set the mast in the socket,

hoist the

sail! Ah, ah, it is too late; faster and faster you near the awful cataract,

and then, shrieking, cursing, howling, praying, over you go. Thousands launch

their barks in smooth water and

realize no danger till on the verge of ruin, boasting all the while to the

last, "When I find out that it is injuring me, then I will give it up." The

power of this habit, I repeat, is fascinating, is deceptive, and men may

go on arguing and coming to conclusions while on the way down to

destruction.

--Taken from Platform

Echoes, John B. Gough. Pages 93-97, 1886.

Back to Biblebelievers.com

One favorite

argument of young men in reference to the use of intoxicating drink is, "When I

find out that it is doing me an injury, then I will give it up." That is

making an admission and coming to a conclusion.

One favorite

argument of young men in reference to the use of intoxicating drink is, "When I

find out that it is doing me an injury, then I will give it up." That is

making an admission and coming to a conclusion. Intoxicating

drink is deceptive in its very nature. It reminds me of the fable of the serpent

in a circle of fire. A man was passing

by, and the snake said to him, "Help me out of my difficulty." "If I do,

you'll bite me." "Oh, no, I won't." "I'm afraid to trust you," "Help me out

of the fire, or it will consume me, and I promise on my word of honor I won't

bite

you." The man took the snake out of

the fire, and threw it on the ground. Instantly the serpent said, "Now I'll

bite you." "But didn't

you promise me you wouldn't?" "Yes, but don't you know it's my nature to

bite, and I cannot help it." So it is with the drink. It is its nature to

bite; it is its nature to deceive.

Intoxicating

drink is deceptive in its very nature. It reminds me of the fable of the serpent

in a circle of fire. A man was passing

by, and the snake said to him, "Help me out of my difficulty." "If I do,

you'll bite me." "Oh, no, I won't." "I'm afraid to trust you," "Help me out

of the fire, or it will consume me, and I promise on my word of honor I won't

bite

you." The man took the snake out of

the fire, and threw it on the ground. Instantly the serpent said, "Now I'll

bite you." "But didn't

you promise me you wouldn't?" "Yes, but don't you know it's my nature to

bite, and I cannot help it." So it is with the drink. It is its nature to

bite; it is its nature to deceive. "What

is it?"

"What

is it?"